Basil Alexander Greshner

| Russian spelling | Василий Александрович Грешнер |

|---|---|

| Born | 31.01.1896 |

| Place | Kibarty, Lithuania |

| Ethnic origin | Russian |

| Religion | Russian Orthodox |

| Father | Alexander Basil Greshner |

| Mother | Olga Greshner (née Dmitrieff) |

| Family | Wife Elizabeth (Lena) Greshner (née Stoodilin), married ca 1927, son Alexander Basil b. 1941; stepchildren Olga, b. 1922, Valentine b. 1923 |

| Contacts | Arrived together with Favst Leoshkevitch, Armen Rowehl, and Edwin Nicholas Rowehl as members of the Gunda crew |

| Arrived at Australia |

from Russia on 10.01.1915 per Gunda disembarked at Geelong, Victoria |

| Residence before enlistment | Winchelsea, Vic., Melbourne; Mount Lyell, Linda Valley, Queenstown, Tasmania |

| Occupation | 1916 seaman; 1924 lineman, 1932 electrician |

| Naturalisation | 1924 |

| Residence after the war | Sandy Bay, Tasmania, Melbourne, New Guinea, Salamaua, Wau, Bulolo, Rabaul, 1932-34 travelled abroad visiting London and Moscow and Semipalatinsk Russia, since 1934 lived in Melbourne |

| Died | 10.05.1980 Surrey Hills, Victoria |

Service #1

| Service number | 7424 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted | 25.01.1916 |

| Place of enlistment | Claremont, Tasmania |

| Unit | 8 Field Company Engineers; 14th Field Company Engineers |

| Rank | Private, Sapper |

| Place | Western Front, 1916-1919 |

| Awards | American DSM; Mentioned in Sir Douglas Haig's despatch |

| Final fate | RTA 22.05.1919 |

| Discharged | 24.10.1919 |

Materials

Digitised naturalisation (NAA)

Digitised service records (NAA)

Digitised Embarkation roll entry (AWM) (Greshnor)

Manuscripts by Basil Greshner - Alexander Basil Greshner' s archives, Nikenbah, Qld

From childhood on

My trip to Russia

Seven Weeks with the Cattle at Sea

Newspaper articles

The Russian trouble. - The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, Qld), 15 May 1905, p. 5 (Assasination of Basil's father)

Blog article

From Russian Anzacs in Australian History:

Basil Greshner's version comes from his memoirs and takes up from when they'd just unloaded the ship [Gunda], 'World War I was on at this time and [we Russians] considered that we were lucky to reach safety'. Greshner claims that, as the ship was not leaving Australian waters again, the sailors all had to leave it -- and 'my mates decided to go to Melbourne. So I took to the bush ... I was fortunate on my two weeks as a swagman doing odd jobs for meals and a night's sleep in the barn. I eventually found my way to Winchelsea and was picked up by a horse-riding farmer who took me to his farm, he made me understand that his son had enlisted early in the war and that he could do with some help. I had to work with him clearing scrub from sunrise till dark. The old lady at the farm was like a mother to me, I had a room to myself and every evening before we went to bed and on weekends she made me read papers, and she explained pronunciations, she also dictated to me and made me write names of everything that she pointed to in the house. ...

'After about three months I felt I would like to go to Melbourne to see my cobbers, so I told my boss and he offered to take me to Geelong and put me on the train, he bought me a suit and underwear and gave me £6.00 and bought my ticket. He said he was sorry to see me go but wished me well. ... In Melbourne at the Russian Consulate I got the addresses of my Russian mates. All of them had found temporary jobs. The Russian consul told us that it was impossible to send us home to Russia and told us that it would be a good idea if we learn to speak and write English and perhaps we could join the Australian Army. [...]

[...] On the following day (1 September [1918]) the 5th Division entered Péronne. Basil Greshner, who was serving in the 14th Field Company of Engineers, was ahead of the advancing troops. His commander wrote, 'this sapper was one of a party detailed to bridge the moat to enable the attacking Infantry to enter the town. After brilliant work on the almost completed bridging, this sapper, on his own initiative, pushed on with the first wave of the attacking troops to make a reconnaissance. Heavy Machine Gun and Rifle fire hampering his work, he proceeded to mop up single handed, capturing 30 of the enemy, and conducting them safely to the rear. His early report of the situation to his Section Officer was of the utmost value and importance.' Greshner was awarded the American Distinguished Service Medal.

[...] Greshner had been working as a linesman and electrician in New Guinea since 1929, and in 1932 from there he set off on the most perilous journey of his life -- to see his mother and other relatives left behind in Russia. He had a visa, which was for a foreign specialist desirous of work in Soviet Russia, although he knew he was potentially at risk as the son of a czarist secret-police chief. As soon as he arrived in Leningrad he was taken to the headquarters of the OGPU (predecessor of the KGB) for interrogation. 'I decided never to show any fear. ... To be able to get away free from them I had to pretend Communist sympathies', he wrote. 'I was determined to see more of Russia by all means, and not from a prison cell.' [...]

Gallery

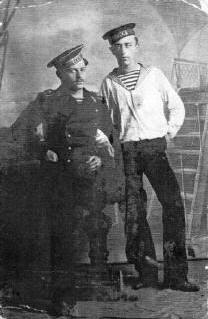

Basil Greshner (right) with a friend, 1912

Courtesy of Alexander Greshner

Basil Greshner in France

Courtesy of Alexander Greshner

Russian Anzacs

Russian Anzacs