Haim Samoilovich Platkin

| Alias | Plattkin; Edward Platt, E. Plattruskin (Platruskin) |

|---|---|

| Russian spelling | Хаим Самойлович Платкин |

| Born | 15.05.1877 |

| Place | Rogachev, Belarus |

| Ethnic origin | Jewish |

| Religion | Jewish |

| Arrived at Australia |

from London on 15.06.1914 per Mantua disembarked at Melbourne |

| Residence before enlistment | Brisbane, Sydney |

| Occupation | 1917 theatrical touring manager |

| Naturalisation | Applied 1917 |

| Residence after the war | Beirut, Lebanon |

Service #1

| Service number | 37448 |

|---|---|

| Enlisted | 3.01.1917 |

| Place of enlistment | Sydney |

| Unit | 46th Battery, 12th Army Brigade |

| Rank | Gunner |

| Place | Western Front, 1918 |

| Discharged | 29.05.1918 in London to join 42nd Battalion (Jewish) Imperial Army |

Service #2 – British Army

| Enlisted | 1918 |

|---|---|

| Place of enlistment | London |

| Unit | 42nd Battalion (Jewish) |

| Discharged | Ca 1919 |

Materials

Digitised application for naturalisation (NAA)

Digitised service records (NAA)

Application for registration of a design by Edward Platt Ruskin for Badge - Class 1 2 3 4 5 6 (NAA)

Digitised Embarkation roll entry (AWM)

Blog article

Newspaper articles

The Cherniavsky brothers. - Daily Standard, 4 August 1914, p. 3.

Arrival of the Cherniavskys. - Daily Standard, 6 August 1914, p. 6.

To aid the wounded. - Brisbane Courier, 6 August 1914, p. 9.

Something in a name. - Sunday Times, Sydney, 13 September 1914, p. 18.

E. Platt Ruskin. A permanent home and institute for the Australian crippled soldiers. Letter to the editor. - Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 5 June 1915, p. 2.

E. Platt Ruskin. Home for crippled soldiers. - Sunday Times, Sydney, 6 June 1915, p. 14.

E. Platt Ruskin. "Lest we forget". Letter to the editor. - Gundagai Independent and Pastoral, Agricultural and Mining Advocate, 24 June 1915, p. 2.

Two of a trade. - Sun, Sydney, 9 June 1916, p. 5.

No. 1 Jury court. - Sydney Morning Herald, 10 June 1916, p. 10.

Buttons and boodle. - Truth, Melbourne, 10 June 1916, p. 6.

H. Platkin. Correspondence. - Hebrew Standard of Australasia, Sydney, 20 April 1917, p. 7.

A.I.F. Rugby team visits Paris of the East. - Courier-Mail, Brisbane, 20 May 1940, p. 4.

Anzac Harry. - Smith's Weekly, Sydney, 13 December 1941, p. 16.

Diggers on leave. - Smith's Weekly, Sydney, 22 August 1942, p. 23.

Ex-AIF man of 80 interned in Syria. - Daily News, Perth, 21 June 1948, p. 11.

Publications

Елена Говор, Белорусские Анзаки. - Białoruskie Zeszyty Historyczne, 2013, no. 40, c. 53-108.

From Russian Anzacs in Australian History:

Haim Platkin was another who made a choice about his identity. A contemporary of Sidney and Elcon Myers, from the same area of Byelorussia, Platkin left there around the same time but went to England, where he lived for the next 20 years, even adopting an 'English' name, Edward Platt. Under this name he arrived in Australia in 1914 as impresario for some Russo-Jewish musicians, and soon became involved in war-charity work, being dubbed by the Australian press 'Father of All the Patriotic Funds'. He enlisted in the AIF under his original name of Haim Samoilovich Platkin as a gesture of solidarity with his motherland but, ironically, he ended up suffering the consequences of the revolution when his beloved Russia let him down.

[...] After his efforts to organise a Russian-Australian unit within the AIF failed, Platkin himself joined up in January 1917 but his experience as a soldier in the AIF was not a happy one: '[The men] have invariably called me Russian anarchist, Russian spy and [I] am generally considered a suspected person.' In early May 1918 he wrote to his commanding officer to set out what had happened, as a preliminary to his request for a transfer to a Jewish unit. Platkin relates that he was recommended for non-commissioned officers' school, but 'by that time news reached Australia of the Russian revolution and it was evident that Russia would sooner or later break down. The members of the N.C.O. school simply boycotted me and as a result I had to discontinue attending it.' Platkin went to the front in November 1917 in field artillery reinforcements as a private, hoping to serve as an interpreter (he knew eight languages). 'Unfortunately', he continues, 'by the time I reached England, Russia had concluded a separate peace. The men of the reinforcement, with which I came over, thought it their duty to have revenge on me. I hardly need explain the treatment I have received.' A cultivated man, he used words as his weapon rather than possessing any real fighting skills, which contributed to the mistrust in him. His battery commander's blunt assessment was: 'He is absolutely useless as a gunner being both incapable and unreliable'.

This mistrust of him went further, however. In February 1918 the War Office in London was stirred up by the discovery that 'certain Australian soldiers have been in touch with Mr Litvinoff, the Bolshevik representative in this country', and that Platkin 'was making complaints as to the way in which he was being dealt with in his unit' to Litvinoff's office. There was alarm also at Australian headquarters, where it was believed that Platkin 'received ... circulars from Litvinoff'. Platkin's visit to Litvinoff only fuelled suspicions already held about him.

Platkin had enlisted in the AIF as a Russian -- using his Russian name instead of the English name (Edward Platt) he had adopted while living in England -- because the war had brought out his patriotic feelings for Russia. Now, being persecuted as a direct result of events in the homeland he had re-identified himself with, and driven to despair, he reached his last resort: 'On hearing of the formation of a Jewish Regiment and being of the Jewish faith I, naturally, had a great desire of being transferred to that regiment' and he asked 'to be given a chance to die an honourable death amongst my own people'. Platkin was finally released from the AIF in May 1918 so he could join the Jewish battalion.

... So, there he was. A man destined to remain an eternal outsider, rejected by the diggers, disillusioned in the Australian army. I was unable to find any record of his return to Australia after this war and wondered what became of him. And that seemed to be that. I little suspected that one day I would come across the following piece in the Adelaide News of June 1948.

'Anzac Harry', who was wounded at Gallipoli while serving with an A.I.F. artillery unit, is in an Arab internment camp at Baalbek (Syria).

'Anzac Harry' whose real name is Harry Platkin, was born in Russia and came to Australia with Wirths' Circus before World War 1.

I believe he took out Australian naturalisation papers before joining the A.I.F. He was demobilised in Egypt and went to Beirut (Syria), where he opened Anzac Harry's Bar on the seafront.

During World War II, he sent £10,000 to Britains Spitfire Fund.

His bar was the first port of call for thirsty men of the 7th Division which fought in Syria and captured Beirut. If a digger were broke, he could always get a drink on the house at 'Anzac Harry's'. ...

Harry is accused of being a Zionist... In fact, he is a Christian and not interested in Zionism.

The article ended with an appeal to the RSL (Returned Services League) to 'make representations to the Lebanese authorities'. This was done without delay, and the prime minister's department, the ministries of Immigration and of External Affairs and the Australian High Commission in London all became involved in an investigation into the case of 'Anzac Harry'.

Gradually the story was uncovered: that he had joined the AIF long after Gallipoli; that Australia had refused to naturalise him in 1917 when he was in the AIF (and he had been informed about this at the time and again, after the war, when he was living in Beirut); that he was 'the proprietor of a notorious drinking establishment which did a considerable trade among British troops during the recent war [the Second World War] until it was put out of bounds by the British military authorities for infringement of drinking regulations', and so on. 'Anzac Harry' was eventually released from the internment camp in 1949.

And yet, this is not just a story about a stateless Russian Jew assuming a false identity; it is the story of how an ostracised man overcame what he was denied and achieved what he aspired to, even if it was only in his imagination.

Gallery

Haim Platkin

A435, 1948/4/2237 (NAA)

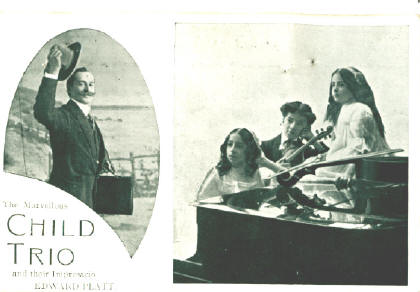

Impresario Edward Platt

Records of Assistant Provost Marshal (AWM)

Russian Anzacs

Russian Anzacs